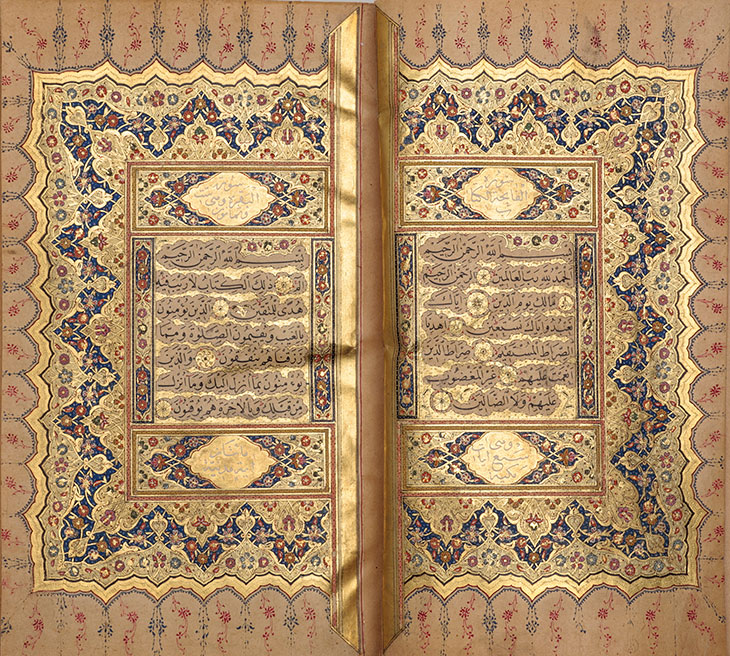

A square vellum Qur’an produced in Valencia in 1199–1200 AD is written in regional Andalusi script by a relatively unknown scribe. Its cover bears a complex lattice structure stained in a burnt ochre that has darkened with age. It is modestly illuminated compared to the shimmering gold on an 18th-century Ottoman paper Qur’an, the naskh script of which is enclosed by sumptuous and fluidly undulating borders featuring a colourful thicket of floral designs.

Pages from a single-volume Ottoman Qur’an (1778), with calligraphy by Hafız Mahmud Celâleddin and illumination by Ibrahim Nazif

The books exemplify something of the range of ages, styles, and origins that we might refer to when speaking about Islamic art, a category that is easily flattened and not necessarily religious. This variety is well documented in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, a group of 28,000 objects including jewellery and armoury, sculptures, textiles and miniature painting. These span a period of close to 1,400 years and, though concentrated in North Africa and the Middle East, also represent southern Europe, China and India.

The collection is the largest of eight that make up the Khalili Collections, some 35,000 works accrued over five decades by Nasser Khalili, a British-Iranian scholar and philanthropist. These include collections of objects associated with the cities of Mecca and Medina, Aramaic documents, Japanese Meiji art and kimonos, and Swedish textiles. Each is of eminent importance in its field and together they offer a global perspective on art and cultural artefacts. Artistic director Waqas Ahmed says, ‘We are aware of the Van Goghs, the Picassos and the Renaissance masterpieces, but how many of us really know about masterpieces from the East or from various parts of Africa, East Asia or the Middle East? The artists are of the same calibre as those we know in the Western canon.’

Carriage cushion cover with reindeer and birds (first half of the 19th century), Herrestads, Scania, Sweden

Offering public access to their property is not typically a priority for private collectors, but Khalili has plans to do just this. Seeking a platform that had international reach and renown, he approached Wikimedia UK with the proposal of releasing high-resolution images of works from his collection, which has been gradually digitised over the past three decades, under a Creative Commons license. Some 1,000 works and counting are now freely accessible on the Khalili Collections website as part of the recently launched ‘Masterpieces of the World’ initiative. ‘The partnership is an important part of our wider, longstanding strategy to make the collections more accessible to art and culture lovers worldwide,’ Khalili has said.

For Wikimedia, the partnership fits happily into the concept of ‘knowledge equity’ that became part of their strategy in 2017, an effort to address its relative neglect of the history and culture of non-Western civilisations. Though the images currently available represent a fraction of Khalili’s collections, they have been selected for their particular historical and cultural significance and, through Wikipedia, ‘Masterpieces of the World’ will offer readable summaries of the extensive research and cataloguing carried out on the works in-house. Of a planned 100 volumes covering the collections, just over 70 are already published. ‘It made sense that this cultural capital is made available to as many people as possible,’ Ahmed says.

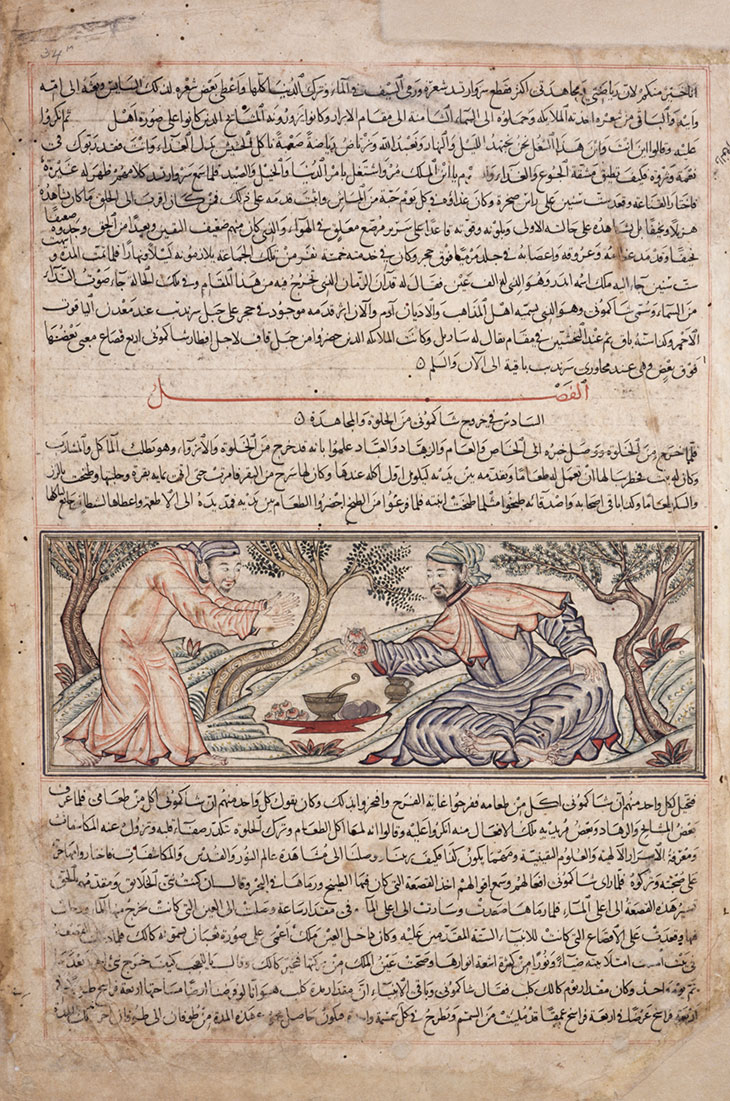

Page with illumination depicting Shakyamuni offering fruit to the devil (from the life of the Buddha) from the Jami‘ al-Tawarikh of Rashid al-Din (MS 727), copy from 1314–15

One work of particular importance that will now be publicly available is a group of 59 folios from the earliest known copy of the ‘Compendium of Chronicles’ (or Jami‘ al-Tawarikh) by the 14th-century Persian court historian Rashid al-Din. Commissioned by ruler of the Mongol empire, Ghazan Khan, it is believed by some to be the first attempt at a world history. The empire’s recent past and Ghazan’s reign are detailed in the first of three extant volumes, with the second looking at the history of various religions, including biblical scenes and chapters from the life of the Buddha, and other events like the legendary Kurukshetra War in India. It is these pages that are held in the Khalili Collection. The final book takes a still wider view at the ‘five dynasties’ of the Jews, Arabs, Chinese, Franks (Europeans) and, of course, the Mongols. With a focus that is both local and global, the compendium speaks both to the ease with which world histories can be warped by a particular perspective and an enduring, historical interest in including and understanding alternative narratives.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze