The story of how works of art and other cultural treasures were saved during the Second World War has been fixed in many peoples’ minds by the renown of the Monuments Men and the Hollywood dramatisation of their role. They made a key contribution, but the reality was of course far more complex and nuanced and involved many others across Europe. A moving exhibition in Rome plots how Italians protected their patrimony during the devastating years of the conflict. This is a timely analysis of individual and communal acts of bravery and foresight, at a moment when, once again, elsewhere in Europe, cultural sites and collections are endangered.

The display in the Scuderie del Quirinale starts with a disturbing document – a handwritten catalogue of Hermann Göring’s collection, open at a page that lists works by Titian, Botticelli, Tintoretto and Veronese among others. Following this, three main narrative threads run though the display: hiding treasures from the Nazis; protecting buildings and particular works of art from the threat of bombing; and restitution after the war was over. The exhibition is also organised around cities and regions – so examples of works stolen from and saved in Turin, Bologna, Florence, Venice, Rome itself and Naples, as well as other centres, are shown.

Installation view of ’Liberated Art: Masterpieces Saved from War, 1937-1947’ at the Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome

Throughout, two especially effective display strategies have been employed. The paintings and other works of art on show are not set in a conventional fashion against politely painted gallery walls, but rather before sheets of wood, intended to evoke the packing cases in which they were either hidden or shipped to Germany. The use of historic film footage and enlarged documentary photographs – with the works of art shown in them displayed alongside – is also especially powerful.

Madonna and Child with Angels (c. 1474), Piero della Francesca. Photo: Claudio Ripalti; © MiC – Galleria Nazionale delle Marche

Some wonderful but perhaps not especially well-known paintings are included, such as Morazzone’s The Forge of Vulcan (after 1599; Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Milan) and Guercino’s Santa Palazia (1658; Pinacoteca Civica, Ancona). Amid these are more high-profile masterpieces, including Piero della Francesca’s Madonna di Senigallia (c. 1474; Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino). This painting was hidden, along with Giorgione’s Tempesta, under the bed of Pasquale Rotondi (1909–91) who was the Sopraintendente of the Marche and one of the heroes of the efforts to secretly store works. He was charged with safeguarding treasures from 1940 onwards and created discreet warehouses in a Renaissance castle, the Rocca di Sassocorvaro near Pesaro, and at the Palazzo dei Principi di Carpegna in Montefeltro. Objects such as the Pala d’Oro from San Marco in Venice were housed in these temporary stores and in total as many as 10,000 treasures were saved as a result of his extraordinary and until relatively recently, uncelebrated endeavours.

Danae (1544–45), Titian. Photo: Luciano Romano; su concessione del Ministero della Cultura/Polo Museale della Campania

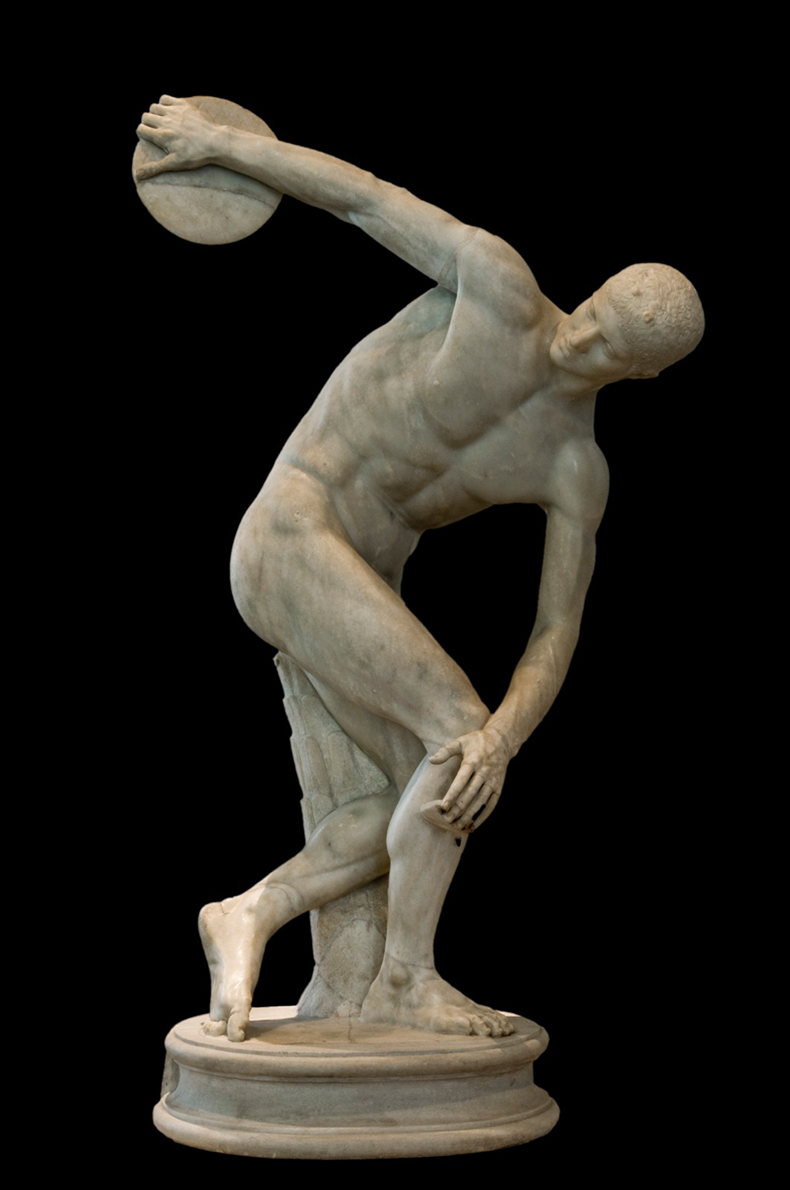

Titian’s Danae (1544–45; Museo e real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples) provides a sensational coda to the exhibition: it was stolen in 1943, hung in Göring’s bedroom and restituted in 1947. Such Renaissance paintings dominate the display, but objects in other mediums are also included: antiquities, sculptures, tapestries, maiolica, books, manuscripts, a globe and music (an autograph score by Gioachino Rossini). The most prestigious ancient work shown is the white marble Discobolus (discus thrower) which is copy of a Greek bronze (second century; Museo Nazionale Romano-Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome). It was admired by Hitler, who considered it represented an ideal example of ‘Aryan’ physique, and a photograph of him in Bavaria with it in 1938 forms the backdrop to the sculpture’s presentation. The previous year, Mussolini broke Italy’s export laws so it could be illegally sold to Germany; the marble eventually returned in Italy in 1948.

Discobolus (second century), Rome. Su concessione del Ministero della Cultura – Museo Nazionale Romano/Palazzo Massimo alle Terme

The exhibition is unusual, as a documentary project and an act of commemoration and thanks – and all the more powerful because of it. It has been very busy, with many visitors in silence contemplating both the enormity of losses and selfless accounts of survival.

‘Liberated Art: Masterpieces Saved from War, 1937—1947’ is at the Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, until 10 April.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze