From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Can anyone resist the extraordinary prices offered for great works of art these days? It seems that even the custodians of financially untroubled historic collections are not immune to temptation. On 19 December, the Detroit Free Press revealed that in 2013 the trustees of the Edsel & Eleanor Ford House on Grosse Pointe Shores had succumbed to the third unsolicited offer from an anonymous private collector and discreetly sold Cézanne’s La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue du bosquet du Château Noir of around 1904 for a mighty $100m.

The canvas will be replaced by a reproduction. This sets the decision to sell rather at odds with the mission of a historic house with an operating endowment of $86m, which prides itself as ‘an authentic witness to the past that inspires, educates and engages visitors through exploration of its unique connections to art, design, history and the environment’. Moreover, the sale highlights the disparity in the US between the ethical guidelines set out for deaccessioning art from museums and those for other non-profit cultural institutions, such as historic houses. The irony is that just down the road the Detroit Institute of Arts heroically deflected the city’s attempts to sell off its masterpieces to settle Detroit’s debts.

Vue sur L’Estaque et le Château d’If (c. 1883–85), Paul Cézanne. Image: © Christie’s Images ltd

In London, meanwhile, Christie’s announced the sale of another great Cézanne from a historic collection – and until recently on long-term loan to a major museum. This is the earlier Vue sur L’Estaque et Le Château d’If of around 1883–85, a work acquired by Samuel Courtauld in 1936 and one of just two of the 10 Cézannes not included in his great bequest to the Courtauld Gallery. His daughter Sydney had married the politician R.A. ‘Rab’ Butler, latterly Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, who died in 1982, and the canvas has been on loan to the university’s Fitzwilliam Museum since 1985.

Cézanne famously claimed that he wanted to ‘make Impressionism something solid and enduring like the art in museums’, and the intense light and dramatic terrain around L’Estaque served him well. Colour was heightened and contrasts sharpened. Here he began experimenting in constructing his landscapes out of overlapping diagonal planes of colour, rejecting conventional perspective in favour of broad horizontal bands of land, sea and sky articulated by the structural planes of rocks and roofs and the framing pines. Already there is a sense of the monumentality and immutability that he sought. The great Impressionist scholar John Rewald described this painting as ‘a work of luminous serenity and soaring lyricism’, and many will agree. It comes to the block on 4 February with an estimate of £8m–£12m but how can it not make far, far more?

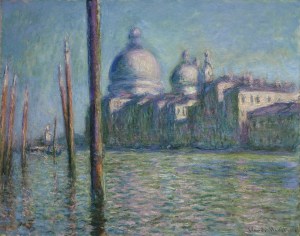

Le Grand Canal (1908), Claude Monet. Image: courtesy Sotheby’s

The seemingly unquenchable global demand for the great names of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art has also encouraged another of Monet’s delectable Venetian views back to auction – and off a museum wall. In June 2013, Sotheby’s London found £19.7m for the artist’s 1908 depiction of the Palais Contarini engulfed in a purply-blue haze. On 3 February, the auction house presents another of his Venetian tours de force, Le Grand Canal (1908), this time with Santa Maria della Salute as the motif. Six paintings exist from this series, and this one, which changed hands in 1989 (for $11.5m) and 2005 ($12.9m), and has been on loan to London’s National Gallery since 2006, is now expected to sell for £20m–£30m.

Surrealist art also continues to attract collectors new and old across the globe, and the buoyancy of this market is reflected by both Christie’s and Sotheby’s offering stand-alone sales alongside their London Impressionist and modern art evening sales. Miró and Magritte are the presiding geniuses of Christie’s Art of the Surreal Evening Sale on 4 February, and indeed this group of eight Magrittes – four oils and four gouaches on paper – constitutes the most important offering of the Belgian artist’s works at auction since that consigned from the collection of his friend, the lawyer Harry Torczyner, in 1998. (All were part of a diverse but distinguished collection that divulged Francis Bacon’s 1960 Seated Figure (Red Cardinal) in New York in November, and which now offloads works by Miró, Modigliani and a Delvaux commissioned by the vendor, as well as Picasso and Fontana.)

Among the Magrittes is the compellingly sinister Les compagnons de la peur of 1942. The wartime date of this canvas, painted during the Nazi occupation of Belgium, is significant, for there is a real sense of foreboding in this near monochrome image of beady-eyed, watchful owls.

Les compagnons de la peur (1942), René Magritte Image: © Christie’s Images ltd

Proud and usually solitary predators, they are huddled together atop a mountain, all possibility of flight now curtailed as they stand rooted – literally – to the ground, part metamorphosed into plants and almost petrified like the rock they stand on. Maybe it is the plants that have metamorphosed. Either way, Magritte was unable to resist exploiting the similarities between leaf and feather – what he referred to as the ‘elective affinities’ between formally related objects.

The title of this widely exhibited painting – like those of many of his works – was drawn from wide-ranging literary sources, not least the detective novels of Rex Stout. This was the title given to The League of Frightened Men when Gallimard published it in French in 1939. It is estimated at £2.7m–£3.5m. Over at Sotheby’s London on 3 February, the transformation relates to a carrot and a bottle. L’explication (1952), the largest of four variations on the theme, is expected to fetch £4m–£6m.

While Magritte and Miró are stalwarts of the Surrealist sales, Marc Chagall is more of a rarity. His early, lyrical Jeune fille au cheval of 1927–29 is a characteristically fantastical and misty-eyed evocation of love and reverie, an apparition of a flower-clad, bare-breasted woman sitting cross- legged on a horse serenaded by an airborne fiddler, set against his beloved hometown of Vitebsk. It goes under the hammer at Christie’s London on 4 February with an estimate of £2.2m–£2.8m.

ARCOmadrid, the heavyweight state-sponsored art fair, has not had an easy ride in recent years as Spanish collectors in particular – both corporate and private – retreat from the contemporary art market. Last year saw fewer exhibitors – still a massive 238 from 32 countries – but dealers reported solid sales at mid-market level (a significant part of the fair’s annual budget is now spent on bringing international collectors as well as museum professionals to the event). Now in its 34th year, the fair runs from 25 February–1 March, and this edition sees the number of participants down to 219, with an unsurprising increase in overseas dealers. The Latin American contingent is stronger than ever, not least thanks to this year’s ArcoColombia section. As well as reinforcing its role as a ‘gateway’ between Latin America and Europe, the fair continues to play to its strengths by encouraging in-depth explorations of the work of one or two artists.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze