From the May issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

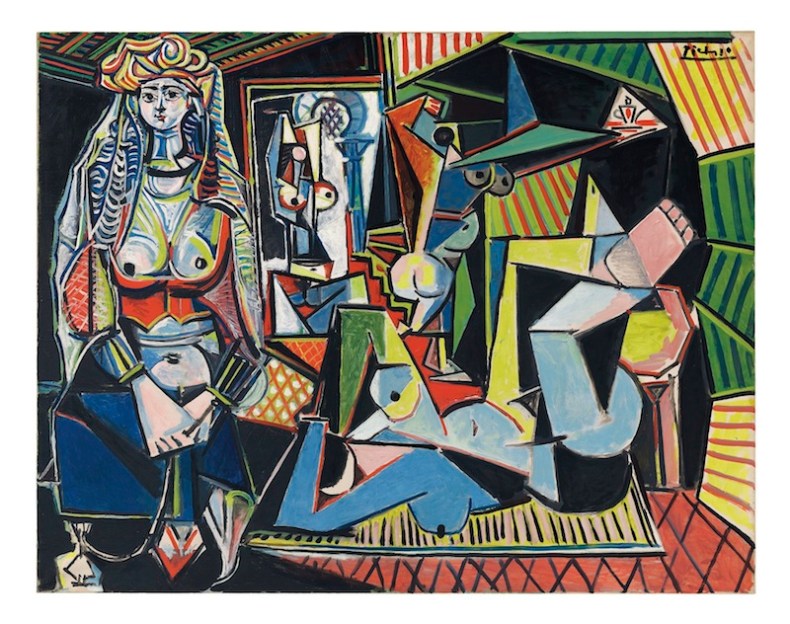

On 11 May, Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’) is offered by Christie’s New York. It comes to the block with what must be the highest auction estimate ever given: $140m. The auction house has also offered the painting’s European consignors a guarantee, meaning they will be paid regardless of the outcome of the sale. Is this a mark of confidence or sheer bravado? After all, the world auction record for any work of art – Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) – is just marginally more, at $142.4m. Either way, the fact that Christie’s is publishing the estimate, and curating a special cross-category sale of 20th-century ‘masterpieces’ around it, leaves no doubt that its target audience is one of rich contemporary art buyers, who measure the desirability of a work not just by its quality and importance but by how much they have to pay for it.

Looking Forward to the Past is the title of this sale, which has been curated by Loic Gouzer, a contemporary art specialist who was astounded to discover that Picasso’s work ‘still looks so relevant and fresh’. His idea is to encourage contemporary collectors to look backwards too, and discover the likes of Mondrian, Schiele and Magritte. In so doing they will swell the ranks of trophy hunters. According to Christie’s global president Jussi Pylkkänen: ‘It has become clear that the many new global collectors chasing masterpieces have been waiting for an iconic Picasso to appear on the market.’ Certainly this 1955 tour de force comes with the reassuring imprimatur of the Victor and Sally Ganz collection, once the largest private holding of Picasso in the US, and which set a new auction record for a single-owner sale when its Picassos and post-war American paintings were sold in 1997. It was even the cover lot – more than doubling expectations to sell for $31.9m. The irony of today’s trophy hunting and ludicrous prices is that the Ganzes were real and passionate collectors, and very comfortably off rather than exceedingly rich. Over 50 years they probably spent no more than $2m on art.

‘Les Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), 1955, Pablo Picasso, oil on canvas, 114×146.4cm, Christie’s New York, Looking Forward to the Past (11 May). Estimate $140m, Enquiries +1 212 636 2000. Image: © Christie’s Images Ltd 2015

In 1956, they near bankrupted themselves by buying all 15 of Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger series – Picasso’s dealer insisted it was all or nothing – and immediately proceeded to sell all but five. Version ‘O’ is the final and most resolved canvas in a series that pays homage both to the artist’s revered Delacroix, who had painted two versions of the subject, and to his friend and rival Matisse, who had died in 1954 and was, in effect, Delacroix’s spiritual heir. Picasso once joked that Matisse had left him his odalisques as a legacy, and here he makes reference not only to Matisse’s orientalism but to his exuberant high colour and pattern-making, too.

It seems that Monet is also high on the shopping lists of these new collectors, and not least his bold, proto-modern series of Nymphéas and watery Venetian or London views. After a raft of huge auction prices (Sotheby’s alone sold 18 works by the Impressionist master last year), Sotheby’s New York is offering six more in its 5 May evening sale. Topping the bill is a 1905 Nymphéas that has not been seen on the market since 1955 (estimate $30m–$45m), and a 1908 view of the Palazzo Ducale (estimate $15m–$20m), a painting restituted to the heirs of its pre-war owner in 1960. Christie’s counters in its Looking Forward to the Past sale with Le Parlement, soleil couchant of 1902 (estimate $35m–$45m).

The Pop Art highlight of the season comes courtesy of Sotheby’s New York’s 12 May Contemporary Art evening sale. The Ring (Engagement)

of 1962 is one of Lichtenstein’s largest paintings of the period, and its first owner was the then 25-year-old Jean-Marie Rossi of Aveline, latterly the doyen of the French antiques trade. He purchased it in 1963 for $1,000. Now $50m is expected (the artist’s auction record stands at $56m).

‘Shakōki-dogū’, Japan, Jomon period (12000–300 BC), painted earthenware, ht 19.5cm, Sotheby’s London, The Soul of Japanese Aesthetics: The Tsuneichi Inoue Collection (13 May). Estimate £70,000–£90,000, Enquiries +44 (0)20 7293 5000

Asian art is the focus in London in mid May, both in the salerooms and in galleries. Refined early ceramics seem to be the order of the day. Eskenazi presents a private US collection of Chinese ceramics from the Song dynasty (960–1279), with prices from $60,000 to around $5m. The highlight here is an imperial Guan dish – one of the few examples remaining in private hands. Sotheby’s London, meanwhile, is offering The Soul of Japanese Aesthetics: The Tsuneichi Inoue Collection on 13 May, a carefully put together holding rich in early Chinese wares. Illustrated is an extraordinary earthenware figure – a shakōki-dogū – from Neolithic Japan.

Made in the Jōmon period (c. 12000–300 BC) around 2,800 years ago, it belongs to a group of hollow figurines believed to have been used in rituals as fertility goddesses and termed goggled-eyed in reference to the sun goggles traditionally worn by the hunting tribes of the north. If still intact, it would have stood around 40cm tall. The imprinted pattern of the raised relief came from rolling a rope or cord over the surface of the clay. After demarcation lines were incised, the voids were then rubbed smooth. These contrasting areas have all been carefully burnished, lending them a lasting lustre. The figure’s black tonality – perhaps created in imitation of bronze – resulted from the oxygen being cut off in the final stages of an open-air firing. Unusually, the well-defined open mouth appears to be speaking (estimate £70,000–£90,000).

On 27 May, Sotheby’s London is also offering the estate of the society beauty Mary, Duchess of Roxburghe (1915–2014). Some 700 lots drawn from West Horsley Place, her retreat in Surrey, have been consigned to auction by her nephew, Bamber Gascoigne. In true country-house-sale tradition, there is everything from old fishing rods, golf clubs and ice skates (estimate £400–£600) to the prerequisite furniture, silver, china and glass – and here, livery, tiaras and court dress (her grandfather was the prime minister Lord Rosebery; her godparents Queen Mary and King George). As for fine art, there are family pictures and portraits, among them three ethereal pencil studies (estimate £20,000–£30,000) for the head of Fortune in Burne-Jones’s The Wheel of Fortune (1883). His sitter was the actress Lillie Langtry, regarded by many as the most beautiful woman in England. Here, too, is Glyn Philpot’s 1917 swagger portrait of the Duchess’s mother, Margaret Primrose, Marchioness of Crewe (estimate £10,000–£15,000). The family diamonds are destined for the Magnificent Jewels sale in Geneva on 12 May.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)