The cream of the art and antiques world once again gathers in the MECC in Maastricht for TEFAF (16–24 March); this year, some 300 dealers from 20 countries bringing a total of around 35,000 objects spanning seven millennia. While the event is divided into its usual eight sections – Ancient Art, Antiques, Design, Houte Joaillerie, Modern, Paintings, Paper, and Tribal – the Modern section for 2019 has been swelled by 13 new exhibitors, out of 28 newcomers to the fair overall. Here is our second instalment of Susan Moore’s picks of the fair – catch up on part one here.

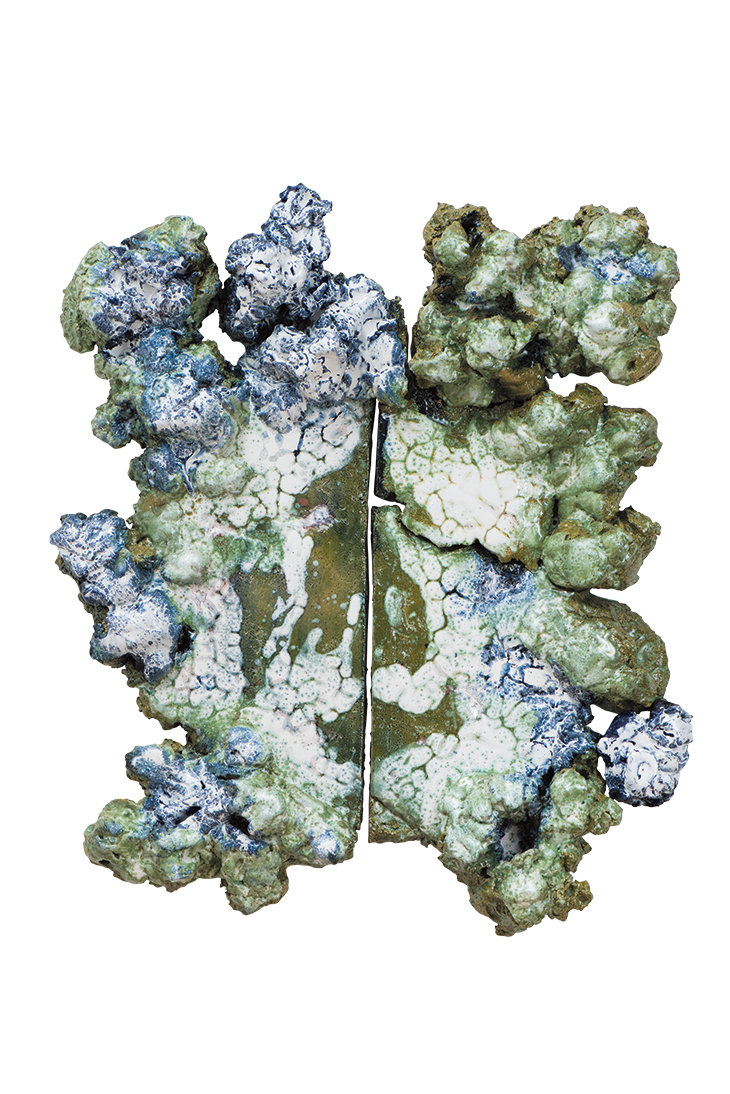

Tabletop (second half of the 16th century), Gujarat, India

Àlvaro Roquette & Pedro Aguiar-Branco, €640,000

This rare Gujarati tabletop is one of only three known examples. Modelled after European furniture prototypes, its decoration is essentially Islamic. The tesserae, made from the highest-quality green turban shell – Turbo marmoratus – radiate from a large central medallion, forming a stylised lotus flower. Inside are small, contrasting nielloed silver tesserae and tortoiseshell dots. It is likely to have belonged to a member of the Portuguese court.

Tabletop (second half of the 16th century), Gujarat, India. Álvaro Roquette & Pedro Aguiar-Branco, €640,000

Marry Mood (2016), Rosemarie Trockel

Sprüth Magers, €450,000

Trockel’s practice is as wide-ranging as it is hard to classify. The renowned German conceptual artist has been making these mirror pieces since 2007, each with a more or less circular central section, often given a platinum glaze that does not, of course, provide a true reflection. These more artisanal fragile objects with tactile and colourful finishes contrast with her earlier use of industrial materials.

Marry Mood (2016), Rosemarie Trockel. Sprüth Magers, €450,000

Side Chair (1970s), Peder Moos

Dansk Møbelkunst, €95,000

Peder Moos falls into that rare category of architect and designer who made his own furniture. Moreover, the Dane was renowned for painstaking craftsmanship and attention to detail. As a result he produced only 30-40 pieces. Although each one was made to order, he would select the woods he wanted to use and let their properties guide him instinctively to create the piece; only after it was complete would he draw a design. Primary woods were chosen for hardness, while secondary woods provided strength and colour. Avoiding nails, screws and varnish, he preferred to turn this self-imposed necessity into a virtue, using dowels and wedges in contrasting darkened wood to dramatic effect, and sand each piece to a fine silken finish. His curvilinear, organic forms are reminiscent of art nouveau but are lighter and more refined. Moos’ sister Marie designed this chair’s original, hand-woven upholstery. A Moos table established a new record price for Nordic design in 2015, selling for over £600,000.

Side chair (1970s), Peder Moos. Danks Møbelkunst, €95,000

Venus (500–200 BC), Chupícuaro culture, Michoacán,

Guanajuato state, Mexico

Martin Doustar, €750,000

The necropolis of Chupícuaro contained many types of ceramic offerings, but none more spectacular than these large female figurines. While this culture is little understood, it seems reasonable to see these distinctive, hand-modelled figurines as fertility figures, given their wide hips and gently swelling bellies, and the bold step-fret patterns of their painted and highly burnished surfaces as an echo of body paint. Newcomer Martin Doustar is exhibiting this second-largest known example of the type in TEFAF’s ‘Showcase’ section.

Venus (500–200 BC), Chupícuaro culture, Michoacán, Guanajuato state, Mexico. Martin Doustar, €750,000

Merli Futuristi (Futurist Blackbirds) (c. 1924), Giacomo Balla

Bottegantica, price on application

Balla’s visualisation of the sounds of city life is well known but in the 1920s he turned to the countryside and landscape. In this blackbird’s song he composes a harmony of sound, rhythm and complementary colour; he used the same composition again to experiment with different colour combinations.

Merli Futuristi (Futurist Blackbirds) (c. 1924), Giacomo Balla. Bottegantica, price on application

Offrande du Soir (1960), Alfred Manessier

Applicat-Prazan, €260,000

Demoralised by the war and the occupation of France, Manessier left for a three-day retreat in a Trappist monastery in 1943 and experienced a religious awakening. He also ‘felt profoundly the cosmic link between sacred chanting and the world of nature’. A visit to Provenance in 1958, where he was fascinated by the appearance and movement of the river Verdon, led him to incorporate abstractions of the Provençal landscape into his mystical works. The result was an intensity of colour and a technique of painting in which slabs of luminous pigment resemble mosaics or stained glass – a medium he also worked in. The themes of the Passion and the Resurrection recur in these paintings, often entitled ‘offerings’ or ‘litanies’. In 1962, this canvas was among the large-format works in the French pavilion of the Venice Biennale, which won him the Grand Prix for Painting – his friend Giacometti won the sculpture prize.

Offrande du Soir (1960), Alfred Manessier. Applicat-Prazan, €260,000

TEFAF Maastricht is at the Maastricht Exhibition and Congress Centre from 16–24 March.

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)