Crystal Bennes heads to St Petersburg in the second part of her series about museum storage collections and the art hidden away inside them

The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg is vast – its building complex of 67,000 square metres is comparable only to the Louvre or the Smithsonian – and its collection of more than 3 million objects (including a numismatic department of some 1.15 million coins) is simply staggering.

Given these numbers, perhaps the museum’s dedication to making its collection as accessible – a mission driven by its director Mikhail Piotrovsky – is somewhat surprising. As part of the Hermitage’s open-stores policy, the collection can be viewed via near-daily tours, which last just under two hours. Including the storage centres, the principal Hermitage complex, and various Hermitage ‘dependencies’, some 30 per cent of the collection is on public display, an impressive figure considering its size.

The first phase of the Staraya Derevnya Restoration and Storage Centre, an enormous, architecturally-muddled complex of buildings north of the city centre, was completed in 2003; the second in 2015. A third phase, designed by Rem Koolhaas, will house the Hermitage’s extensive library holdings and costume collections across the road and is tentatively scheduled for 2018.

Render of the entire Hermitage stores complex including a third phase designed by Rem Koolhaas.

Inside the main building, which also houses conservation, research, and numerous offices, orientation is near impossible. Signs are scarce and the corridors are all painted in the same shade of taupe. The occasional arrow marked out on the floor in tape along our route suggests that even the guides get confused from time to time.

Once inside the individual rooms, navigation becomes easier, and the care with which the building has been designed is much in evidence. These spaces provide a notable contrast to the experience of viewing the collection in the Winter Palace, where the opulent surrounds are often distracting and abysmal lighting conditions make it difficult to see the paintings properly. The purpose-built facilities are free of these problems and it’s a pleasure to look closely at the works here.

Open furniture stores at the Hermigate. Photo courtesy the State Hermitage Museum

It’s fascinating to try and work out why some of the works have remained in storage, although the country’s complicated political history makes this a difficult talk. Many objects have not yet been properly catalogued and considerable gaps in knowledge of the collection remain. Nevertheless, curiosities abound…

Too many objects, not enough space: Adoration of the Sacrifice frescoes (14th century), Pskov

During the Great Northern War with Sweden (1700–21), the Russian armies used sections of church walls to reinforce barricades and trenches. Discovered during a Hermitage excavation shortly after the Second World War, these delicate, 14th-century frescos depicting the Adoration of the Sacrifice have been pieced together and remounted on concrete panels. While the frescoes have never been displayed in the Winter Palace, they were shown in a 2011 exhibition on the art of the Russian Orthodox Church at the Hermitage Amsterdam. According to my guide, about a third of the Hermitage’s collection is archaeological and there’s simply not enough space for it in the museum.

Adoration of the Sacrifice fresco (14th century), Pskov. © Crystal Bennes

19th-century Russian portraiture, a collection in transition: Portrait of P.A. Zubov (1873), Ivan Petrovich Köller-Viliandi

Since the 1990s, the Hermitage has expanded its Winter Palace exhibition space to take over the nearby General Staff building across Palace Square, where its noted, if not uncontroversial, collection of French Impressionist art now hangs. While 19th-century Russian portraiture will eventually also be housed in the General Staff building, for now a selection of this 3,000-strong collection is on changing display in the stores. Among the works is this striking portrait of the noble Platon Alexandrovich Zubov by the Russian-Estonian painter, Ivan Petrovich Köller-Viliandi. In 1912, the family residence became the Russian Institute of Art History and after the October Revolution it passed, presumably with the family art collection, to the new government.

Portrait of P.A. Zubov (1873), Ivan Petrovich Köller-Viliandi. © State Hermitage Museum

The unwanted gift: an Ottoman tent presented by the Turkish Sultan Selim III to Catherine the Great

According to my guide, this richly decorated field tent is one of the stores’ most popular objects with visitors. Presented to Catherine by Selim III in 1793, the tent was briefly erected in the Winter Palace and then packed away for over 200 years. It is now housed in a room of its own, on specially constructed scaffolding that protects the wool and embroidered silk panels.

Ottoman tent presented by the Turkish Sultan Selim III to Catherine the Great. Photo courtesy the State Hermitage Museum

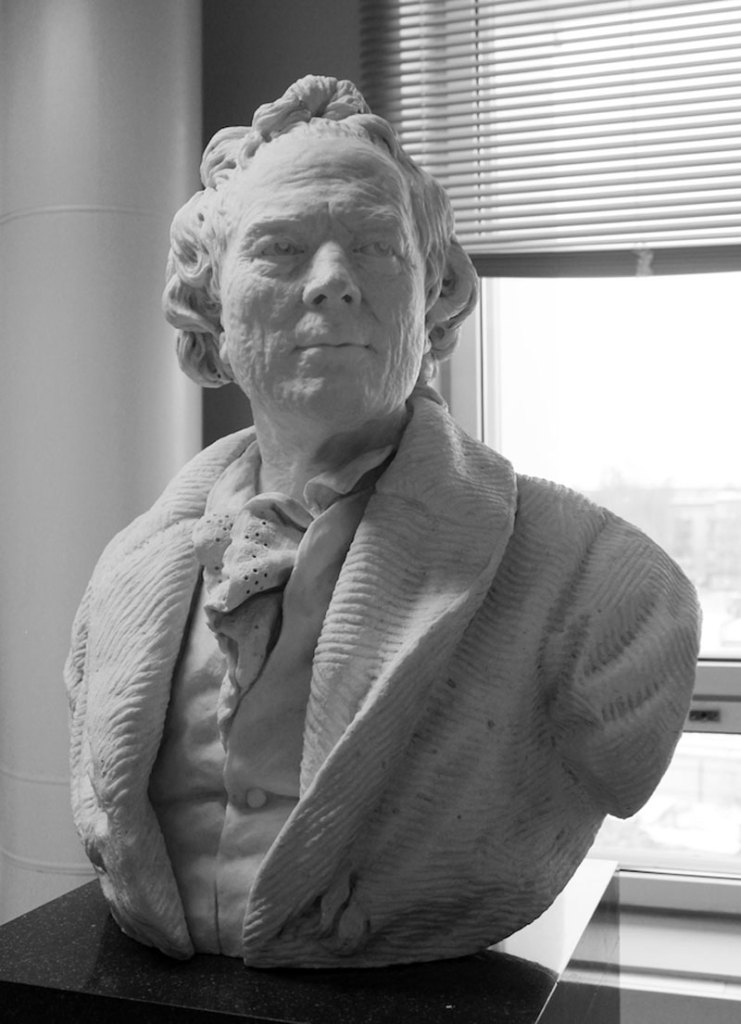

A copy or the real deal? Gluck (1777), Jean-Antoine Houdon or 19th-century copy

Catherine II was an important patron of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s; many examples of his work are dotted throughout the Winter Palace, including busts of Catherine, the Comte de Buffon, and Voltaire. This bust of the celebrated composer Christoph Willibald Gluck is a more complicated affair – hence its appearance in the stores.

Houdon’s original plaster bust was exhibited in the Salon of 1775, before the creation of a marble version in 1777, which was later installed in the Paris Opéra (and destroyed in the fire of 1873). A bronze version was purchased from Houdon’s studio in 1775 by Carl August, who was soon to be Prince of Weimar (now in the Schlossmuseum, Weimar). No other marble copies by Houdon survive. While the contact between Houdon’s studio and Catherine’s court during the years 1773 to 1783 makes one wonder if an undocumented copy made its way to Petersburg, this bust entered the Hermitage collection only in 1937. Although the Hermitage’s inventory notes the bust as a 19th-century copy after the original, the question of its provenance and authorship remains tantalisingly unanswered.

Gluck (1777), Jean-Antoine Houdon or later copy. Photo © Crystal Bennes

The Weimar bronze version of Houdon’s Gluck. Photo © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

A neglected collection, 19th-century Russian icons: the Virgin of Smolensk (1812), Andrey Leontyev

While the icon has occupied a central position in Russian religious and domestic life since the country’s adoption of Christianity in 988, examples from the 13th to the 17th centuries have attracted the most attention. While the Hermitage collection includes a sizable proportion of 19th-century icons, they have never been exhibited in the Winter Palace, displayed instead within the stores.

One beguiling example, seen below, is the Virgin of Smolensk by Andrey Leontyev, in which an image of the icon of the virgin hovers above the town of Smolensk. According to the Hermitage, the Prince of Smolensk, better known as General Kutuzov, during the war of 1812, carried this icon. Contemporary accounts also indicate that, on the eve of the Battle of Borodino, Kutuzov had paraded around a camp a 17th-century copy of the original Virgin of Smolensk icon, said to have been deposited in the cathedral of Smolensk in 1101.

The Virgin of Smolensk (1812), Andrey Leontyev. Photo courtesy the State Hermitage Museum

Pietà redux: a 19th-century copy of Antonio Montauti’s Pietà

This 19th-century copy of a c. 1734 Pietà by Florentine sculptor Antonio Montauti was bought by Prince Leonid Vyazemsky on a trip to Italy. The sculpture was later installed in the family crypt underneath the church of Demetrius of Thessaloniki, built in 1884 near their estate in what is now the Voronezh region. The church had fallen into ruin by 1938, when a Hermitage expedition team discovered the site and transferred the sculpture to the museum stores for restoration. When it was found, the sculpture was completely blackened – it had been in a fire at some point between the church’s closing and its later rediscovery. Two black patches have been left on the statue in reference to show condition in which it was originally found. Curators have ascribed a possible attribution of Girolamo Masini (1840–85), but this remains unconfirmed.

A 19th-century copy of Antonio Montauti’s Pietà. Photo courtesy the State Hermitage Museum

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://zephr.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)