From a liquid band of inky black brushstrokes in Landscape near Felpham (c. 1800), Blake has us looking across an open space towards a far bank of blue trees. A looming windmill is lightly drawn in on the left, one of its sails formed from a gap of paper left in the transparent wash of the grey-blue sky. Nestling in the distant trees are the square tower of a church, a second narrower tower, and a few low-lying cottages. In the autumn of 1800, as lines written around the time of this landscape suggest, Blake experienced glittering light and sunbeams in a visionary mood: ‘I stood in the Streams / Of Heavens bright beams / And Saw Felpham sweet’. Bathed in sun and sitting on yellow sands to draw and write, he described ‘Each grain of Sand / Every Stone on the Land’ as ‘Men Seen Afar’.

The buildings in this watercolour are those of what the poet William Hayley called the ‘marine village’ of Felpham on the Sussex coast, where Hayley lived, and where Blake and his wife Catherine came to reside under his auspices for a period of three years between 1800 and 1803. The church is St Mary’s, the other tower that of Hayley’s house, The Turret. Blake’s cottage is the one on the far right nearest the slanting shafts of light (the counterparts to the blank wedge of sail). ‘Felpham is a sweet place for Study,’ Blake wrote to his friend the sculptor John Flaxman, ‘because it is more Spiritual than London. Heaven opens here on all sides her Golden Gates; her windows are not obstructed by vapours.’

By 1800 the Blakes were hard up. Employment from well-meaning patrons in Sussex came as a relief, even though Blake’s optimism was later to cool. It was Flaxman who introduced Blake to Hayley. In turn, Hayley connected him to the Reverend John Johnson, and to the Earl and Countess of Egremont who (independently) bought works in the ensuing decades. This is the network explored by ‘William Blake in Sussex: Visions of Albion’, at Petworth House, where the Egremont Blakes have been since the 19th century. The show emphasises the central place of the Sussex period in Blake’s career, and its enduring impact on his later work. Together with key commissions from the Felpham years, we are given various moments when the landscapes or memories of Sussex seem to reappear in Blake’s images long after he had returned to London.

But the question of place in Blake is not so easily answered. Look again at the landscape. Are we standing on a road? On the edge of a body of water? Only what might be a faintly sketched rider on horseback and a fence give the fields away. The blue stretching between us and the buildings seems now as much aqueous as earthy, reminding me of the strange blending of earthiness and wateriness that Blake achieved in a different mood in his large colour print showing Newton at work with a compass on the sea floor. In a poem for Anna Flaxman, he wrote of Felpham as somewhere that defied the gulf separating living and dead, a sort of no-place that collapsed distances in space and time: ‘The Ladder of Angels descends thro the air […] You stand in the village & look up to heaven / The precious stones glitter on flights seventy seven / And my Brother is there & My Friend & Thine’. Blake’s brother had died in 1787.

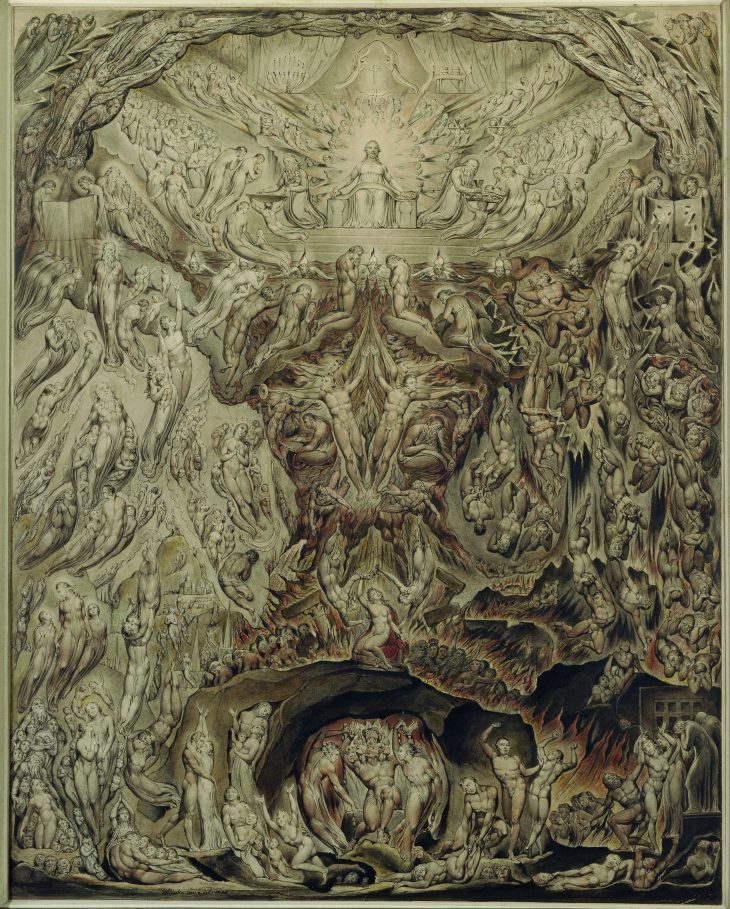

A Vision of The Last Judgement (1808), William Blake. Courtesy Petworth House and Park, West Sussex

What is ‘place’ for Blake when the cottage at Felpham is, to his mind, a ‘shadow’ of angels’ houses, or when (in Henry Crabb Robinson’s paraphrase) ‘Oxford Street is in Jerusalem’? One way to approach the problem might be to return to an old formalist concern, and attend to the ground of Blake’s pictures, that is, to the substrate or background against and with which forms or figures are made visible. In Winter (c. 1820–25), painted for the fireplace of the Rev. Johnson’s Norfolk rectory and on display here next to other temperas done for Hayley’s library, body and ground collapse in on each other. The hoary, druidical figure is barely distinguished from the striations of grey and white that animate the whole visual field, as if fronds of beard and veins of fictive marble were one. Ambiguities and oscillations of figure and ground are taken to extremes in A Vision of the Last Judgment, commissioned by Elizabeth Ilive, Countess of Egremont in 1808 (by which time she had left the Earl to live separately in London). With its central axis of hell’s cave, rising sea of fire, and luminous throne of Judgment, the picture is like a womb, a ‘uterus’ as the exhibition’s curator, Andrew Loukes, points out. I see many wombs, or pockets, or cells, each enclosing different figural units. To the left and just above the cave there are spires (Chichester again?) and domes nestling between or peeking out from what Blake in his prose description, the manuscript of which is also on display here from the private archive of Lord Egremont, called ‘Green Hills’. But ‘between’, ‘out from’ – such prepositions fail when trying to describe space here. One minute a hill is a hill, the next it is an enclosing cell, a sort of vestibule, containing a gathering of saved souls. In this corner of the picture, as elsewhere, tessellations of cloud, earth and stone destabilise a hierarchy of foreground and background, of edge and interior, and leave us, for all the clarity and distinctness of Blake’s vision, unsure quite where we are.

Winter (c. 1820–25), William Blake. Courtesy Petworth House and Park, West Sussex

One can see why Blake was drawn to the patron of this strange work. Elizabeth Ilive was the daughter of an impoverished printer from Oxford whose brief marriage to the 3rd Earl spanned the duration of Blake’s time in Sussex. Her remarkable life and career is documented in a supplementary display in the North Gallery (specially enlarged by the 3rd Earl in the 1820s to house his collection of contemporary British art). A portrait by Thomas Phillips (for whom Blake also sat) shows Ilive with a diagram of the cross-bar lever she designed for lifting stones and the medal it won her at the Society of Arts. She set up a laboratory at Petworth in 1798. A case full of receipts for artists’ supplies and scientific equipment – glass and earthenware retorts, imploding bottles, Magdeburg hemispheres, a bottle of yellow powder – conveys an experimental disposition she must have shared with Blake. An earlier version of the first picture she commissioned from him, the darkly fiery, gold-flecked Satan Calling up his Legions, was included in Blake’s one-man exhibition in 1809. He described it as ‘a composition for a more perfect Picture, afterward executed for a Lady of high rank. An experiment Picture.’

‘William Blake in Sussex: Visions of Albion’ is at Petworth House, West Sussex, until 25 March.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.